Respiratory Aid in Various Settings: Exploration of Accessory Muscle Breathing in Infancy, Palliative Care, and Beyond

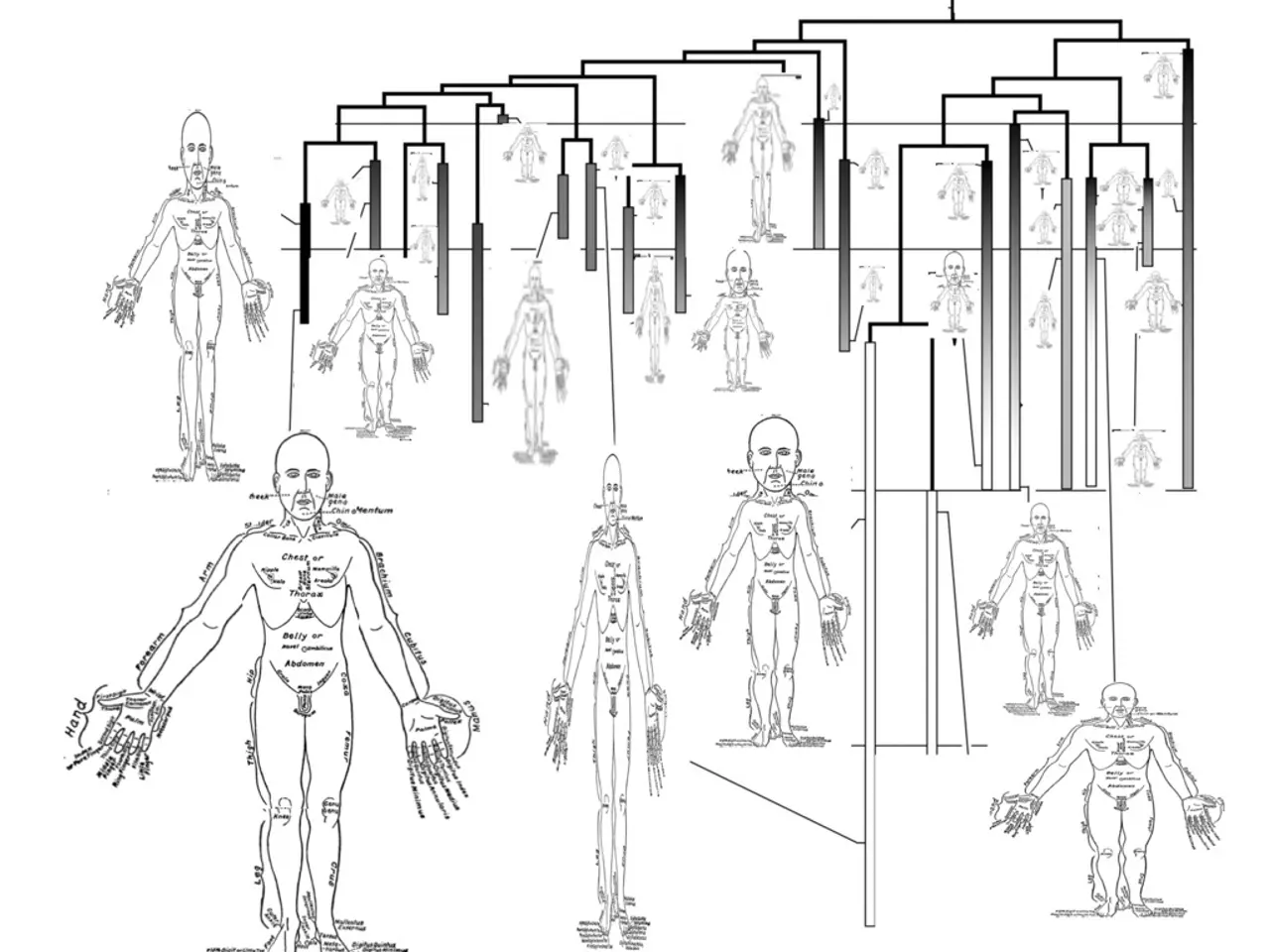

In the human body, accessory muscles play a crucial role in supporting ventilation during increased respiratory demand or difficulty breathing. These muscles, which include the sternocleidomastoid, scalene muscles, trapezius, serratus anterior, and sometimes the pectoral muscles, primarily assist during inspiration by elevating the ribs, clavicle, and sternum to increase thoracic volume [1][5].

These accessory muscles become active in various conditions or situations, such as exercise, respiratory distress or diseases, and pathological lung conditions causing impaired ventilation [1][2][4]. During physical exertion, accessory muscles like the scalenes, sternocleidomastoids, trapezius, and serratus anterior help expand the thoracic cavity beyond the capacity achieved by the diaphragm and external intercostals alone [1][5]. In conditions like asthma attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, or severe respiratory infections, when primary muscles cannot meet the oxygen demand or there is airway obstruction, accessory muscles become active to aid ventilation [2][4].

For individuals with COPD, a doctor may recommend pursed-lip breathing to reduce reliance on accessory muscles. However, in people with COPD, the diaphragm and intercostal muscles can be at a disadvantage due to lung over-inflation, leading to the use of accessory muscles [2][4].

In addition, accessory muscles may also be activated in young children under general anesthesia due to their inability to control breathing and underdeveloped intercostal muscles, leading to more dramatic breathing deterioration [3].

It is essential to note that involuntary breathing requires airway resistance muscles like the skeletal muscles of the tongue, hyoglossus, styloglossus and stylohyoid muscles, glottis, larynx, pharynx, and smooth bronchi muscles.

In the end-of-life care setting, shortness of breath may be indicated by the activation of accessory muscles and reversed breathing patterns.

In summary, accessory breathing muscles support ventilation during increased respiratory load (exercise) and respiratory compromise or distress (disease states such as asthma or COPD) when primary muscles cannot maintain adequate ventilation alone [1][2][4][5]. If a person appears to be working harder than usual to breathe, it is crucial to contact a doctor as soon as possible.

References: [1] Miller, R. D., & Smith, M. L. (2018). Miller's Anatomy. Elsevier. [2] Huang, J. T., & Huang, H. L. (2018). Respiratory physiology: the essentials. Elsevier. [3] Anesthesia for children. (2018). British Journal of Anaesthesia, 121(1), 1-13. [4] West, J. B. (2010). Respiratory physiology: the essentials. Elsevier. [5] Leigh, J. S., & Patton, K. T. (2014). Physiology: an introduction to the human body. Elsevier.

- Accessory muscles such as the scalenes, sternocleidomastoids, trapezius, and serratus anterior are activated during conditions causing impaired ventilation, like asthma attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, or severe respiratory infections.

- For individuals with COPD, a reliance on accessory muscles can occur due to lung over-inflation, which may necessitate a doctor's recommendation of pursed-lip breathing to reduce this reliance.

- In some cases, such as young children under general anesthesia, accessory muscles may become active due to an inability to control breathing and underdeveloped intercostal muscles, leading to more dramatic breathing deterioration.

- In end-of-life care, shortness of breath may be indicated by the activation of accessory muscles and reversed breathing patterns.